The OECS Commission assesses the impact of BREXIT and reflects on the lessons of Brexit for regional integration in the Caribbean and in the OECS in particular.

We have all been saturated with news and views on the British vote to exit the European Union in the past week and there is much more to come by way of analysis and revelation as things unfold. Not unexpectedly, the Brexit has created the opportunity for those who are opposed to regional integration efforts all around the world to find comfort. Not unexpectedly in the Caribbean there are also those who seek to mimic the British and are also calling for exit of sorts from regional integration.

These calls are nothing new – almost fifty years ago Sir Arthur Lewis, the intellectual author of OECS integration, was very clear about the main impediments to the realization of regional integration:

“What has stood in the way of Federation is not the sea… The real stumbling block has been the opposition of small local potentates. The larger and more far seeing capitalists realize the immense advantages that would flow from Federation, and advocate it. But it is the small potentate – planter or merchant [one might add: politician] – fearful that his voice, a big noise in a small community will be unheard in a large federation and has so far succeeded in preventing it.”

Whatever position one may hold on the Brexit question, it is now becoming painfully clear that this divorce will be a long, protracted, painful process in which much will be lost.

Ian Bremmer of the Eurasia Group summed it up adequately:

“You are talking about the diminishment of the most important alliance of the post war order, the transatlantic relationship which was already before Brexit at its weakest since World War II. You’re talking about not only the removal of the UK from the EU but you’re also talking I think reasonably likely about the eventual disintegration in further part of the UK itself. And you’re talking about a severe diminishment of what the European Union actually means, its footprint globally, its common values, and its ability to continue to integrate.”

There is much work to be done to determine the implications and impact of Brexit on the Caribbean’s relations with Europe and with Britain but the situation provides us with a special opportunity to reflect on the lessons of Brexit for regional integration in the Caribbean and in the OECS in particular.

Lesson 1 – Connecting the people to the process

From all of the analyses of the post referendum public sentiments, it is clear that Brexit was a rejection of an integration process that the average person in the street did not apparently understand. Google’s announcement that the most searched queries in the aftermath of the referendum were “What does it mean to leave the EU?” and “What is the EU?” is a very disturbing indication of the failure of public education on the matter. A referendum assumes that the electorate is provided with extensive information with the pros and cons thoroughly argued so as to arrive at an intelligent decision. As electoral campaigns tend to go, the battle is often to win the hearts more than the heads of voters and the results of referendums do not always suggest that there has been that deep introspection.

From all of the analyses of the post referendum public sentiments, it is clear that Brexit was a rejection of an integration process that the average person in the street did not apparently understand. Google’s announcement that the most searched queries in the aftermath of the referendum were “What does it mean to leave the EU?” and “What is the EU?” is a very disturbing indication of the failure of public education on the matter. A referendum assumes that the electorate is provided with extensive information with the pros and cons thoroughly argued so as to arrive at an intelligent decision. As electoral campaigns tend to go, the battle is often to win the hearts more than the heads of voters and the results of referendums do not always suggest that there has been that deep introspection.

The moral of that Brexit story for the OECS is that connecting the people to the process must be a continuous commitment not simply to giving and sharing information but also an obligation to listen to people. Integration processes must connect not only with people’s dreams and aspirations but also listen to and address their fears.

The OECS Communications Strategy which is currently being rolled out in phases seeks to put this capacity to share and to listen in place. It involves among other initiatives, the launch of a new interactive website that links social media with a communications platform that enables outreach to the widest universe of stakeholders from the highest to the humblest across the full spectrum of economic and social interests.

Lesson 2 – Engaging and Empowering the Youth

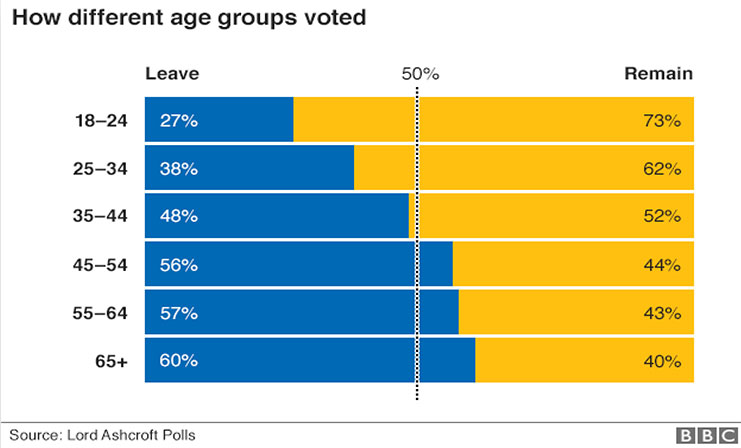

One of the most glaring contradictions exposed by the Brexit referendum is the near perfect correlation of age with voting position and also with educational level. The Wall Street Journal reported that 68% of those voting to leave were persons who did not graduate from high school; while 70% of those voting to remain in Europe were college graduates. As the BBC graph shows, the relationship between voting in favour of Brexit and age is strong – young persons voted to remain; older persons voted to leave. The unfortunate reality of this situation is that those who voted to remain will have to live with the consequences of Brexit much, much longer than those who instigated it.

The lesson of that reality is the importance of empowering and engaging youth. Regional integration projects are essentially about creating a very different future – by removing the barriers within the geographic space, they alter the mental geography and consequently the range of opportunities available. It also points to the difference in perception that education makes – higher education predisposed most British youth to seeing themselves as European. It can be argued that narrow insular identities are inherently restrictive if they embody a closed mentality. The challenge of that experience to us in the region is whether we are educating our youth to see themselves as global citizens with a Caribbean identity that is rooted in their national consciousness. Accomplishing this is a complex task that requires a fundamental reengineering of our education systems and how this can be done (easily) will require a separate discussion. Suffice it to note that the nexus of age and education points to an emerging global divide – older and less educated citizens have experienced the disadvantage of globalization while the younger more educated citizens recognize the opportunities that it presents. For a regional integration effort to be meaningful to the people, it needs to connect that divide.

With the world becoming increasingly smaller and interconnected through new and emerging technologies, we must work through a new education paradigm to empower youth to recognise that they are indeed the custodians of a better tomorrow. History has demonstrated the power of youth to affect change through the shaping of public debate and policy. Whether it be the Young Women’s Christian Organisation pioneering race relations, labour relations and the empowerment of women across early America, to radical student activism reviving the issue of racial-apartheid in conservative South Africa in the 1980’s, a collective youth voice has always remained omnipotent.

The cost of inaction in not educating and empowering youth far outweighs the cost of action. The long term potential human cost from right wing and nativist groups across Europe being emboldened by the Brexit move illustrate this point. While the Caribbean does not share this exact same dynamic, the fact remains that until seventy years ago a fragmented European continent was at war almost continuously for a thousand years. Any moves that result in a discord to the unity enjoyed by Europe over recent years will only help fuel ill-informed nationalistic groups, present in every European nation. These groups by their very nature frequently attract pliable young people andthe disenfranchised seeking a populistcause often manifested in a myopic anti-immigration platform. It is from this platform in which they seek to vent and justify their call for isolationist policies and a homogenous society devoid of those from other cultures, ideals and backgrounds. This could have serious and direct implications for the Caribbean diaspora.

Lesson 3 – Respecting the Sovereignty of Member States

The issue of the sovereignty of Member States is always a touchy matter because at some point in every integration process – even when it is limited in scope – the process will necessitate a decision on whether or to what extent national priorities will prevail or yield to regional imperatives. And not every proposition may be a win-win.

How this is handled invariably revolves around the calibre of political will around the table. It takes leaders of exceptional vision to look beyond the immediate to the strategic and to invest their political capital in the decision. History has recorded such moments. It was demonstrated by Nelson Mandela when he decided to throw the support of his new Government behind the South African Springboks and the sport of Rugby – both endemic symbols of Afrikaner culture. By this singular act of courage he won over many Afrikaans to the rainbow nation. It was demonstrated in the OECS in the signing of the Treaty of Basseterre 35 years ago when leaders such as Maurice Bishop of revolutionary Grenada found common ground with an infinitely more conservative Eugenia Charles of Dominica. Despite deep differences, they were able to commit to a Treaty that has stood the test of time out of which institutions of demonstrable value have emerged.

In the Brexit scenario, Brussels was portrayed in some quarters as an overarching and overbearing supranational authority that trampled on the traditions and rights of national governments. Regional organizations such as the CARICOM Secretariat and the OECS Commission need to be mindful of such perceptions and to ensure that our way of working engages Member States in manner that is respectful of their differences. At the OECS Commission, the approach is to maintain an ongoing dialogue with national authorities and to shape the agenda jointly with execution being done through engagement of expertise within both Commission and Member States.

Lesson 4 – A Facilitating Role for the Commission

The fourth lesson is also related to the portrayal of the European Commission as an intrusive and imposing bureaucracy by the forces opposed to integration.

The OECS Commission has adopted a more facilitating role in its management of the integration agenda. The Councils of Ministers meet twice a year in face to face mode but have agreed to meet as often as is necessary via video conferencing. Working Groups involving experts from the respective portfolios in Member States meet as often as needed largely via video conferencing to prepare harmonized policy briefs, develop project proposals, and define specific collaboration actions. The OECS Commission in this context plays a facilitating role in convening these meetings but the agenda is constituted by all participants prior to the meeting.

By working synergistically with line ministry expertise both process and product are more acceptable to Member States.

Lesson 5 – The Four Freedoms are Indivisible

The fifth lesson is expressed in the warnings of the European leadership that the four freedoms on which the European Union is built are indivisible:

- Freedom of movement of people

- Free circulation of goods

- Free movement of capital

- Free movement of services.

This indivisibility makes it difficult for countries to “cherry pick” those elements that they deem more favourable to them while rejecting others. This challenge is also at the heart of the difficulties faced by the CSME and to a lesser extent the OECS Single Space. Big businesses welcome the opportunity for the free circulation of goods and capital because it gives them access to a much bigger demographic. In the case of the OECS, the Anglophone OECS is a demographic of 600,000 and with addition of Martinique that figure moves to 1 million. Free movement of goods and capital within such a market – in the context of the small states that constitute it – is a real boon to doing business. The free movement of people however is a different challenge as the same arguments are raised whether in Brexit or CSME – the coping ability of Member States for a large influx of persons from economically stressed parts of the union to another. Certainly the free movement of services is hampered without the free movement of people and it is the genuinely free movement of people that will ultimately create a regional mind-set. As more and more people travel to work, lime and reside in different parts of the economic union, their mental geography changes and they begin to belong to all parts.

What has compounded the European situation has been the unusual wave of migration resulting from wars and instability in adjoining regions. In the case of the Caribbean, it can be argued that the prosperity and global “relevance” of countries such as (Antigua & Barbuda?), Sint Maarten and Cayman Islands is underpinned by their relatively large migrant populations.

Conclusion

As the drama of Brexit unfolds, it is imperative that we go deeper in our analysis of that experience for two reasons: firstly in order to better re-position ourselves and advance our interests/relationships and secondly in order to learn the lessons of the European experience to improve our own integration effort. From the OECS perspective, there is an additional political dynamic that must be brought to center stage and that is the consequence of Brexit for the British Overseas Territories. Brexit means that they will be losing their EU citizenship and access to all opportunities that emanate from the EU because of someone else’s decision (the British Electorate). The people of Anguilla, the British Virgin Islands, and Montserrat did not have a say in this decision and, given the extent of what is at stake here, it is incumbent on the OECS to stand in solidarity with these Member States in the assertion of their right to some self-determination on this question.